A previous version of this post stated that the Rt. Rev. C. FitzSimmons Allison was the active Episcopal bishop of South Carolina in 1999. Bp. Allison retired from the diocesan seat of South Carolina in 1990, but continued active teaching and speaking for many years, and remained a bishop in the Episcopal Church until he joined the ACNA in 2022 at the age of 95. Today Bp. Allison serves as a bishop in residence in the (ACNA) Anglican Diocese of South Carolina. The Rt. Rev. Edward Salmon was the bishop diocesan of South Carolina in 1999.

This is a new kind of post on Detestable Enormities — what I’m calling, for lack of a better word, a vignette. Vignettes will be sort of self-contained histories of specific incidents. When we talk about polity, it’s easy to be abstract, but given that laws and ecclesiastical events that affect everyone are not created in a vacuum but in response to actual conditions, I think it’s important to have these events on our radar to help us understand how the whole system developed. We’ll then be able to refer to these vignettes when making broader points.

We’ve been in an extended series on clergy discipline in TEC vs. in ACNA for a while now, and a core thing I’ve been emphasizing is this: because ACNA came most directly out of TEC, when its framers were drafting canons they were not doing so from scratch but from a status quo. Understanding the shape of both churches’ disciplinary systems today, as well as their attitudes more broadly, requires understanding each group’s reaction to what the system was—last time everyone was under one roof.

As you may remember, TEC took on a massive revision of Title IV in 1994. This revision implemented a uniform disciplinary system for priests and deacons across all dioceses for the first time ever. Under this system, an accused priest would face trial in his or her own diocese, and could appeal the result up to a provincial court.1

Today we’ll look at the first time that happened under post-1994 Title IV. What happened, and what did people think of it?

Warning: the stories in this post, while not graphic, touch on difficult issues including suicide and sexual abuse. If these subjects are tough ones for you, please proceed only with caution.

What happened?

In the turbulent 1990s, the Rev. James R. Hiles was a priest at two churches in the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts.

The first, St. Paul’s Church in Brockton, was a parish founded in the late nineteenth century. Hiles became its rector in 19752 and launched several lively institutions under its aegis, including the Evening School of Christian Studies3 and St. Paul’s Kitchen,4 a soup kitchen that remained important in the area for many years after the events of this article. The second, the Church of Our Saviour in Milton, was founded around the turn of the twentieth century to serve a growing working-class Irish population in the area.5 By the turn of the twenty-first, it was operating as a mission church, with Hiles as its vicar.

Brief diversion: missions vs. parishes

Most if not all Anglican jurisdictions make a distinction between two kinds of churches: missions and parishes. Though terms and details may vary a little from diocese to diocese, the main principle is this: parishes are financially self-supporting, and call their own rector and elect their own vestry; missions are not and do not. Missions’ finances are dealt with by the diocese, and their leadership is much more directly governed by the bishop.

Any given church may fall in or out of mission status at different times in its life, depending on circumstances. A new church plant might start as a mission and eventually become a parish once sustainable; an ailing parish might become a mission to avail itself of more diocesan support.

In the Episcopal Church, the priest that the bishop puts in charge of a mission is classically called the vicar.

Back to Massachusetts

In 1990, a member of the Church of Our Saviour who had died in 19856 bequeathed $2 million to the mission through probate. The mission, however, would not pass this sum into the usual diocesan structures, even though the diocese is responsible for handling finances of mission churches. The dispute continued in probate court for several years, with the mission and the diocese both claiming a right to control the sum.7

As probate ticked on, more was happening in the wider Diocese of Massachusetts. In 1993, its diocesan convention passed resolutions stating that it would ask General Convention to consider the removal of “obstacles to ordination for qualified candidates who are living in committed same-sex relationships” and the creation of a supplementary liturgical resource for the blessing of same-sex unions—while specifying that any such liturgies would not “impos[e] upon any ministers of this church the obligation to assent to its provisions nor obligations of functioning under them.”8 (Remember that Massachusetts the state was an early adopter of their position on this topic. That same year, Massachusetts became one of the first jurisdictions to allow second-parent adoption by a person of the same sex,9 and in 2004 the state became the first in the Union to allow same-sex marriages outright.10)

This did not please those in the diocese who disapproved of church support for same-sex relationships. In response, St. Paul’s Church decided to begin withholding its parish assessment to the diocese — the fee that all parishes must pay annually to support diocesan services.11

A new bishop

A few months later, in 1994, the Diocese of Massachusetts elected the Rev. M. Thomas Shaw, SSJE, as its bishop coadjutor. Shaw, the former superior of the brothers at the Society of St. John the Evangelist in Cambridge, leaned liberal on the presenting social issues but enjoyed a wide base of support, winning a surprise election victory on the first ballot.12 Recall that bishops coadjutor will eventually become the bishop diocesan — they have the right of succession upon the diocesan’s retirement, death, or other inability to serve.

But a very serious event was about to seize the Diocese of Massachusetts: the suicide of its bishop diocesan, the Rt. Rev. David Johnson. The news of his death on January 15, 1995, propelled Shaw to the diocesan seat and utterly shocked the diocese. The situation worsened when, days after Johnson’s death, Bp. Shaw and the diocese had to communicate to the public that it had become clear to them that Johnson had engaged for many years in exploitative extramarital conduct.

It is clear that Bishop Johnson was involved in several extramarital relationships at different times throughout his ministry, both as a priest and bishop — at least some of these relationships appear to have been of the character of sexual exploitation. … Detailed information about these relationships is still lacking. While some suspected such behavior, unfortunately no one possessed the factual information necessary to have made these situations known in any venue where appropriate action could have been taken; this is, sadly, not an unusual set of circumstances when people of prominence are involved.

Bp. Shaw explained to reporters that the diocese had come to certainty about this through new contact with women Johnson had exploited. He created a group to respond to any other victims of sexual exploitation whom he encouraged to come forward.13

Thus began a rough 1995 for the Diocese of Massachusetts, which continued with stressful diocesan reorganization and layoffs amid “serious budget constraints.”14 Shaw circled back around to the matter of the $2 million bequest to the mission at the Church of Our Saviour throughout the year, trying and failing multiple times to get Hiles to “use his influence” as vicar of the mission to persuade its committee to end probate litigation and put it under diocesan control, as was expected for all mission finances. By year’s end, Shaw’s frustration with Hiles had mounted. According to Hiles, Shaw summoned him to his office in December and there, getting nowhere with Hiles yet again, lost his temper, accusing Hiles of being “stubborn, a bully, and a liar,” throwing a pen at him, and threatening to remove him as vicar of Our Saviour. Needless to say, St. Paul’s was also still not paying its assessment.15

Title IV revision takes effect

Now we must widen our perspective back to the whole Episcopal Church. The 1994 General Convention had enacted a massive revision of Title IV that completely reimagined and standardized discipline for priests and deacons across all dioceses. The revision also significantly expanded the ways to make a complaint and the criteria for who had standing to bring complaints, including all the way down to a single individual in the case of allegations of crime, immorality, or conduct unbecoming of a minister.

The massive revision, though passed in 1994, was scheduled to go into effect only after January 1, 1996 — mostly to give dioceses time to implement it. One other provision of the revision is worth mentioning: a re-opened window to make complaints that under the previous Title IV would have been allowed to expire.

For Offenses, the specifications of which include physical violence, sexual abuse or sexual exploitation, which were barred by the 1991 Canon on Limitations (Canon IV. 1.4.)[, c]harges may be made to a Standing Committee or the Presiding Bishop, in the case of a Bishop, no later than July 1, 1998.16

This meant that a two-year period was opening where victims of misconduct could bring charges that would not have been possible for single persons to bring previously.

Returning to Massachusetts, a complaint of this very type was lodged against Hiles on March 26, 1996. The lay woman complainant had been a parishioner of Hiles’ at Trinity Church in Copley Square, where Hiles previously worked, and was herself married to the rector of another Boston-area church. She eventually worked for Hiles at the Church of Our Saviour when he became its vicar.17 According to the complainant’s letter to Bp. Shaw, for five years in the 1970s Hiles had had an adulterous sexual relationship with her, culminating in an abortion.18

Following this, the diocese took swift action according to the new Title IV canons:

Shaw immediately passed the allegations to the standing committee of the diocese, who were newly responsible for intake.

The day following receipt of the complaint (March 27), Shaw summoned Hiles for a meeting, where he placed Hiles under a temporary inhibition — a new method of pausing a cleric’s ministry while the disciplinary process unfolded. During the inhibition, Hiles could not function as a priest, communicate with the complainant, discuss any elements of the case with anyone outside his spouse and spiritual or legal counsel, or attend any activities of the Our Saviour mission or the St. Paul parish.

Two days following receipt of the complaint (March 28), Shaw and the Rt. Rev. Barbara Harris, bishop suffragan, wrote to all clergy in the diocese informing them of the allegations and the inhibition against Hiles.

Sixteen days following receipt of the complaint (April 11), the standing committee convened to perform their new duty of asking the question, “if the facts alleged are true, did a canonical Offense occur?” They answered it “yes,” ordering an investigation.19

The reaction

News of this did not go over well at Hiles’ churches, who believed Hiles was being targeted by Shaw. In the immediate aftermath, the junior warden of St. Paul’s claimed that the charges against Hiles were “a direct result of our opposition to the diocese.” The vestry wrote in a letter to parishioners that “the action of Bishop Shaw is obviously a response to [our] forceful rejection of his novel theology, religious coercion and dictatorial threats to reclassify St. Paul's as a mission church.” What’s more, on March 28 — two days after the complaint was received, and one day after Hiles was inhibited — St. Paul’s decided by unanimous vote to attempt to separate themselves from the Diocese of Massachusetts.20

Shaw visited both Our Saviour and St. Paul’s that Sunday, March 31 (Palm Sunday). At both churches, congregants yelled at and openly insulted the bishop, refusing to take communion with him or his attendant staff. Canon Edward Rodman there claimed that any previous diocesan discussion of making St. Paul’s a mission was completely independent of the abuse allegations against Hiles or the conservative views of the parish, instead citing the fact that St. Paul’s had not paid its assessment in years, was in arrears on loans and pension contributions, had a shrinking population in an urban area, and may not be financially viable on its own for much longer.21 Shaw expressed frustration: “A woman has allegedly been terribly abused, and people don't seem to be concerned about that, or even concerned about the possibility that these allegations have happened.”22

For Hiles’ part himself, he absolutely denied the allegations. In fact, he denied them so strenuously that in May of 1996 he brought the matter before secular courts, suing not only Shaw but each individual member of the standing committee and the complainant herself. In total he brought sixteen counts, roughly covering the following:

Defamation, against the complainant and Shaw;

Conspiracy, against the complainant, the bishops, and the diocese;

Interference with contractual relations, against Shaw;

Civil rights violations, against Shaw and the standing committee;

Negligence, against the bishops;

Loss of consortium and intentional infliction of emotional distress, against all of the above;

Assault and battery, against Shaw (because of the thrown pen).23

Hiles’ central claim in his lawsuit was that the complainant had conspired with the diocese and invented false charges of sexual abuse to provide the diocese with a way of getting rid of him, and getting their hands on the $2 million bequest at Our Saviour. He stated by affidavit that “the allegations levelled against me by [the complainant] are entirely false.”24 Shaw, according to Hiles’ suit, was bringing to bear a modern notion of sexual misconduct in order to get what he wanted out of Hiles.

… the drive of money and power have brought the current “buzzword” of sexual misconduct into the picture, with the entire diocesan establishment mobilized to destroy [Hiles] for its own ends.

(Ribadeneira, “Ousted priest sues bishop, accuser,” quoting from Hiles’ suit)

Hiles’ filing of this suit in secular court led the standing committee to add further charges to the Title IV process. In the summer of 1996, once their investigation was complete, the standing committee’s issued presentment against Hiles consisted of four charges:

Immorality;

Conduct unbecoming a member of the clergy;

Violating canonical confidentiality requirements before presentment (by filing the secular suit);

Violating canonical restrictions on filing secular suit “for the purpose of delaying and hindering” Title IV action.25

With a presentment issued, the matter was ready for ecclesiastical court.

The courts have their say

The parallel ecclesiastical and secular court actions are a little confusing, but worth examination, so bear with me.

The next year, in April 1997, the complainant’s motion in the secular court to dismiss Hiles’ claims against her was addressed. The judge in charge of that motion dismissed Hiles’ counts of defamation and conspiracy against the complainant. Most of the other counts were sent to summary judgment, where the judge dismissed them as well on First Amendment grounds — the courts, said the judge, could not get involved with an internal disciplinary matter of a church. Two claims survived and were sent to the court: the loss of consortium, and the assault and battery by Shaw (who, recall, allegedly threw a pen at Hiles).26

Not long after, the ecclesiastical Title IV court of the Diocese of Massachusetts heard the case against Hiles. On May 14, 1997, they found Hiles guilty and recommended that he be deposed (defrocked) from the priesthood. Hiles appealed the finding to the next court identified by Title IV — the appeals court of Province I. But they upheld the diocesan court’s opinion, and Shaw deposed Hiles by March 25, 1998.27

Back in the secular courts, Hiles appealed the findings of the initial district court. In March of 2001, their ruling came down with something for everybody. Hiles, they said, could indeed not sue the Diocese of Massachusetts for defrocking him, since the internal church discipline process is untouchable to them on First Amendment grounds. But, he could sue the bishops and the complainant for defamation and conspiracy. This court argued that, supposing the complainant’s claims of Hiles’ abuse were false and defamatory and that the diocese conspired with her to get Hiles, that would not be okay simply because the defamation and conspiracy took place within a religious context. Hiles would have to have the ability to sue to bring the matter before a court, because such acts would be “secular acts” if they happened.28

The diocese objected to this and appealed, this time to the Supreme Judicial Court, the highest court in Massachusetts. The appeals court’s ruling had opened important questions like:

Can a priest accused of sexual abuse sue someone who complains to the diocese — maybe even the victim — for defamation?

Can a priest accused of sexual abuse sue the diocese for, upon receiving such a complaint, taking up a church discipline case against the priest, and/or for publicizing the fact it is doing so?

Can a priest use the secular courts to block, in advance, any church proceeding that may have him removed for sexual abuse and force the litigation of the accusation into the secular courts instead?

A number of eyes watched this case in 2001-2002 Massachusetts because of its implications for something else.

In August of 2002, the Supreme Judicial Court ruled that, contrary to the appeals court’s finding, Hiles could not sue the complainant or the diocese for making the abuse allegations against him known publicly. The complainant’s letter to the bishop accusing Hiles of misconduct “is inextricably part of the Church disciplinary process,” wrote the court, and “[Hiles’] conspiracy claims are not secular. They require the court to inquire into the motives of these defendants to determine whether the Church's disciplinary procedures were properly invoked”. This they could not do, because of the First Amendment. The sole claims to survive: Hiles’ loss of consortium, and his allegation that Shaw assaulted and beat him when he threw the pen during their heated meeting concerning the $2 million bequest at Our Saviour back in 1995.29

Ripples were felt instantly, within and without the Episcopal Church. The Boston Globe reported that the decision “could effectively insulate the [Catholic] Archdiocese of Boston from defamation claims for identifying clergy members of sexual abuse,” and that, according to the complainant’s lawyer, “the ruling should make victims of clergy abuse feel confident they will not face a retaliatory lawsuit should they seek help from their church leaders.”30

By the end, Hiles had faced the Title IV courts and the secular courts, and came away with victory from neither.

What did people think?

So the first instance of a priest exercising the full post-1994 Title IV trial process, including trial and appeal, had come and gone. What did it all mean?

From a certain angle in the diocese, it meant clear continuity of intent from the beginning of Bp. Shaw’s tenure. Thrust early into his position by the devastating consequences of his predecessor’s sexual exploitation, Shaw signaled early in his episcopate a willingness to receive reports of sexual misconduct in the diocese. In this sense, without even needing to opine on whether conspiracy existed, it is not surprising that very quickly after the Title IV revisions enabled a new class of reports to be brought, one was brought to Shaw. When the diocese made public statements about the charges, it grounded its behavior not in mismatched social stances but in what the new Title IV required of them: “the decision to suspend Father Hiles with pay while the charges against him are investigated is the same procedure followed in other professions, including medicine, law enforcement and education, where public safety is at stake.”31 Outside the diocese, and certainly for Roman Catholics, the follow-through and legal precedent set by the Episcopal diocese were an encouraging example for how churches could respond to allegations of sexual misconduct, quite apart from the issue of social stances taken by Massachusetts Episcopalians — some of the most liberal of the bunch.

But for many other onlookers, even though many separate entities found Hiles in the wrong in one way or another outside of just Shaw, the liberal social views Shaw represented unavoidably colored their perception of events — and indeed their perception of the Title IV reforms themselves. The congregation at St. Paul’s was unwilling to separate the diocese’s consideration of the allegations against Hiles from the diocese’s acceptance of liberal social stances, attributing Hiles’ discipline and defrocking to diocesan retribution for their own conservative ones. The result, for them, was a perceived incursion of diocesan power into the independent realm of their congregation. An interview with the senior warden showed the close link in the congregation’s mind between the two: “We, the congregation, built this church… at this point, whatever the diocese does is irrelevant to us because we don’t recognize their authority,” she said, also saying, “Reverend Hiles dared to challenge church authority and this is how they got him.”32

The very structures of Title IV were brought in for blame outside the congregation as well. Popular conservative Anglican commentator David Virtue wrote of the inseparability, for him and others, of Title IV’s protective structures and liberal social stances with contempt:

… [Shaw filed] 25-year-old trumped up sex charges against the Rev. Hiles. Fr. Hiles was found guilty in a closed ecclesiastical court by a bunch of women priests who could write the film score for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Queen.

How is it possible then that flimsy, unsubstantiated charges going back more than half a person's life time could be dredged up and used against him, especially when homosexual behavior, which the church universal has always deemed morally wrong not only goes unpunished but is actually lauded and upheld as godly behavior?33

More than this, Hiles and the congregation at St. Paul’s were the recipients of support by several bishops. In 1997, after the Diocese of Massachusetts court recommended that Hiles be defrocked, St. Paul’s declared that they were affiliating themselves not with the diocese but with the Episcopal Synod of America (more on this movement another time). The ESA had formally refused to recognize Hiles’ defrocking, denying the validity of the Title IV process; and they sent the Rt. Rev. Edward MacBurney, retired bishop of Quincy, to act as the bishop over St. Paul’s — without asking permission of Bp. Shaw to minister in his diocese.34

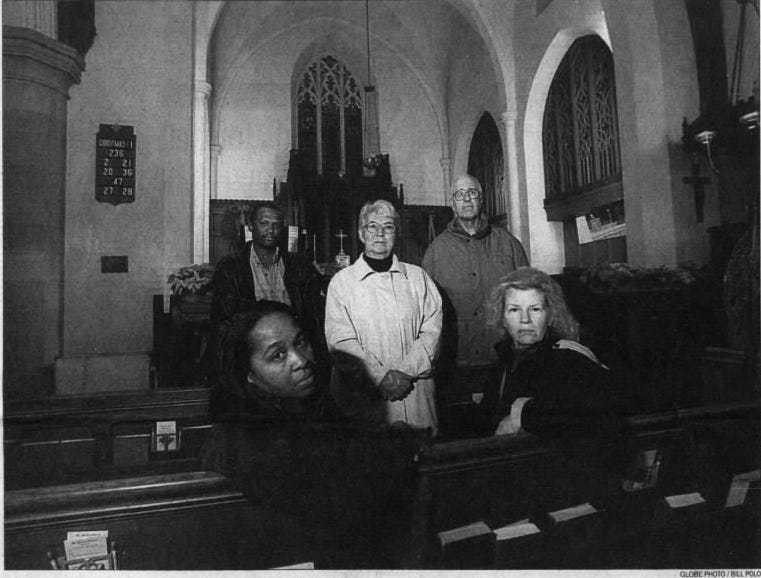

And during the litigation initiated by Hiles outlined above, there was actually even more litigation. After a new diocesan canon came into effect in 1998 that required parishes who had not paid their assessments for three years to become missions under control of the bishop, St. Paul’s was made a mission, and its formal leadership came under the diocese. When Hiles, now defrocked, and the former wardens, now dissolved, would not give keys to the property, the diocese got a court order for them to vacate.35 They did so — and counter-sued the diocese for the property, moving their Sunday celebrations to the sidewalk in front of St. Paul’s.

On the sidewalk they got further episcopal support from bishops willing to transgress diocesan lines. In April of 1999, the Rt. Rev. A. Donald Davies (formerly bishop of Dallas, then of Fort Worth, then of the Episcopal Missionary Church, which split from the Episcopal Church in 1992) confirmed some 30 people at St. Paul’s at Hiles’ invitation.36 In May, the Rt. Rev. C. FitzSimmons Allison (retired bishop of South Carolina) entered the diocese to celebrate at St. Paul’s without Shaw’s permission and vaunted it in interviews, affirming that he “definitely broke canon laws” and that “it would be a badge of honor to be censured by the House of Bishops” for it.37 Allison’s disappointment was palpable when Shaw ignored him.38

Not all those engaged in conservative Anglican media were pleased with these developments. An unhappy letter to the editor in The Living Church lamented these bishops’ lack of focus on the serious issue of sexual misconduct:

… the former rector of St. Paul's, Mr. Hiles, was found guilty of sexual misconduct by an ecclesiastical court of his peers (lay and ordained) and was relieved of his sacerdotal responsibilities. Yet, instead of resigning from his parish, he has used his “cult of personality” to manipulate those under his pastoral care.

We have witnessed the tragic misuse of power in places such as Waco, Texas, and Jonestown, Guyana. Given this situation, I was shocked by Bishop Allison's comment that while Mr. Hiles and his congregation “might feel isolated in the diocese (of Massachusetts), they had a lot of sympathy and support in the worldwide Anglican Communion.” Support for what? The sexual abuse and misconduct of a priest? Support for the misuse of his pastoral responsibility? Or support for focusing on keeping his job and position instead of trying to help his parishioners to undertake the difficult work to try to remain in relationship with their bishop, their diocese, the Episcopal Church, and the worldwide Anglican Communion? Bishop Allison should know better. Given the pain caused by Mr. Hiles, Bishop Allison's grandstanding for the ESA while turning a blind eye to clergy sexual misconduct lacks pastoral sensitivity, and comes at much too high a price.39

In a terse response to this letter, Allison faced the issue of the alleged sexual misconduct head-on and dismissed it, and its Title IV implications, summarily: “the charges against Fr. Hiles were allegations dating from more than a quarter of a century ago, and which charges Bishop Coburn had dismissed as unfounded.”40

After St. Paul’s lost its court battle to remove the church property from the diocese in 2000, they affiliated with the Anglican Mission in America (AMiA) under Bp. John Rodgers.41 At some point, the church moved out of AMiA; Hiles was consecrated a bishop in the Anglican Church in America, a continuing jurisdiction, at 85 years of age in 2013.42 Hiles died in 2021.43

In the Episcopal Church, “province” means “a group of dioceses in a geographic area.” Today the Episcopal Church has nine provinces:

New England

International Atlantic

Washington

Sewanee

Midwest

Northwest

Southwest

Pacific

Latin America

“Province” in this sense should not be confused with another more general use of that term to mean “an entire church” — such as when speaking of member provinces of the Anglican Communion.

“A Brief History,” St. Paul’s Parish in Brockton MA.

James L. Franklin, “3 Hub area churches offering education programs for adults,” The Boston Globe, September 5, 1977.

James L. Franklin, “At Brockton Church, Meal Includes Serving of Dignity,” The Boston Globe, April 15, 1983.

“Irish church leaders to meet in Hub,” North Adams Transcript, via Associated Press, October 24, 1988.

“Obituary for Harriet MEARS,” The Boston Globe, July 5, 1985.

Hiles v. Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts, 437 Mass. 505 - Mass: Supreme Judicial Court 2002

Jay Cormier, “Massachusetts Adopts Resolutions on Blessings of Same-sex unions, Ordination of Homosexuals,” Episcopal News Service. November 23, 1993.

“2 Lesbian Surgeons Receive Mass. High Court’s OK to Adopt Child,” The Los Angeles Times, via Associated Press, September 11, 1993.

Pam Belluck, “Massachusetts Arrives at Moment for Same-Sex Marriage,” The New York Times, May 17, 2004.

Mark Mueller, “Brockton Sidewalk to Play Host to Episcopal Church Schism,” Boston Herald via VirtueOnline, May 14, 1999.

Nan Cobbey, “Massachusetts Elects Bishop Coadjutor on the First Ballot,” Episcopal News Service. March 24, 1994

Jay Cormier, “Massachusetts Begins Healing Process in Wake of Bishop's Suicide, Revelations of Extramarital Relationships,” Episcopal News Service. February 9, 1995.

“In Midst of Transition, Diocese of Massachusetts Struggles with Bishop's Suicide,” Episcopal News Service.

Hiles v. Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts, 51 Mass. App. Ct. 220 (Mass. App. Ct. 2001)

1994 Constitution & Canons, IV.14.4.3.

Diego Ribadeneira, “Ousted priest sues bishop, accuser,” The Boston Globe, May 14, 1996.

Hiles v. Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts, 51 Mass. App. Ct. 220 (Mass. App. Ct. 2001). I believe that it is inappropriate to call an extramarital sexual relationship between a priest and a lay worker at a church merely “adulterous” because of the coercive nature of perceived clerical spiritual authority (and potentially some form of employment authority); the two parties are not on the equal footing that usually underlies the definition of adultery rather than outright exploitation. However, the court records use this language describing what the complainant reported herself, and, lacking the text of the original complaint, I do not wish to potentially put words in the complainant’s mouth about her own perception of the situation.

Hiles v. Diocese, 437 Mass. 505, 773 N.E.2d 929 (Mass. 2002)

Shirley Leung, “Church Battles Bishop: Episcopal parish charges retaliation,” The Boston Globe, March 30, 1996. There is a little confusion about whether this was the first time St. Paul’s had attempted to secede from the diocese. Some other sources claim that they attempted to do this the previous August (1995), but did not try to move forward with it. St. Paul’s history of itself claims that they removed themselves from the diocese in 1993 (though to me, that date more represents the time they ceased paying their assessment to the diocese).

“Bishop of Massachusetts Greeted with Anger,” The Living Church, April 21, 1996.

“Parishioners give a rebuke to bishop,” North Adams Transcript, via Associated Press, April 1, 1996.

Hiles v. Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts, 51 Mass. App. Ct. 220 (Mass. App. Ct. 2001)

Hiles v. Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts, 51 Mass. App. Ct. 220 (Mass. App. Ct. 2001)

Hiles v. Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts, 51 Mass. App. Ct. 220 (Mass. App. Ct. 2001)

Hiles v. Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts, 51 Mass. App. Ct. 220 (Mass. App. Ct. 2001)

“Priest Found Guilty,” The Living Church, May 3, 1998.

Hiles v. Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts, 51 Mass. App. Ct. 220 (Mass. App. Ct. 2001)

Hiles v. Diocese, 437 Mass. 505, (Mass. 2002)

John Ellement, “Ruling protects church in priest suit,” The Boston Globe, August 16, 2002.

Diego Ribadeneira, “Episcopal Diocese denies priest’s charges of greed,” The Boston Globe, May 15, 1996.

Caroline Louise Cole, “A spirited fight between church, diocese,” The Boston Globe, January 24, 1999.

David Virtue, “Some Opening Comments,” DVirtue236 mailing list, July 11, 1999.

“Episcopal Synod of America Elects President,” The Living Church, June 14, 1998.

“Order to Vacate Church Issued,” The Living Church, April 11, 1999.

“Continuing Bishop Confirms 30 at St. Paul's, Brockton, Mass.,” The Living Church, April 25, 1999

“Traditionalists Raise the Stakes by Challenging Authority of Diocesan Bishops,” Episcopal News Service, May 26, 1999.

“Episcopal bishop disappointed he was not disciplined by superiors,” Dallas Voice, via Associated Press, July 9, 1999.

Mark S. G. Nestlehut, “An Unwise Visit,” The Living Church, July 4, 1999.

C. FitzSimons Allison, “Faithful Parish,” The Living Church, August 1, 1999. Bp. Coburn was Shaw’s predecessor’s predecessor as the bishop of Massachusetts, and was unrelated to the specific Title IV case brought in 1996.

“Historic Mobile Parish Added to AMIA List,” Episcopal News Service, October 3, 2000.

“The Right Reverend James Randall Hiles consecrated Bishop Suffragan of the Diocese of the Northeast of the Anglican Church in America,” St. Paul’s Parish in Brockton MA.

“Bishop James R. Hiles (STH’58),” BU School of Theology.