Here we are again in our series on church discipline. So far when it comes to clergy misconduct, we’ve seen Title IV in the Episcopal Church in two main forms: before 1994 (learn more here) and after 1994 (learn more here). For patient ACNA readers (thank you for sticking with me on this extended digression through Episcopal history!), recall that at this point, those who would become ACNA and those who would continue in TEC were still together under one roof — and the major Title IV revision of 1994 would go on to provoke different reactions in different factions that would continue to be at play throughout and following the separation.

More on that in a coming article. But first, we have some loose ends to take care of. In this article, we’ll talk about the initial reactions to the 1994 revisions and some follow-up changes that General Convention made to them the next time they met in 1997.

In particular, the changes focused in on a group who had gotten by relatively untouched in the otherwise-comprehensive 1994 revisions: bishops.

Bishops on the hook

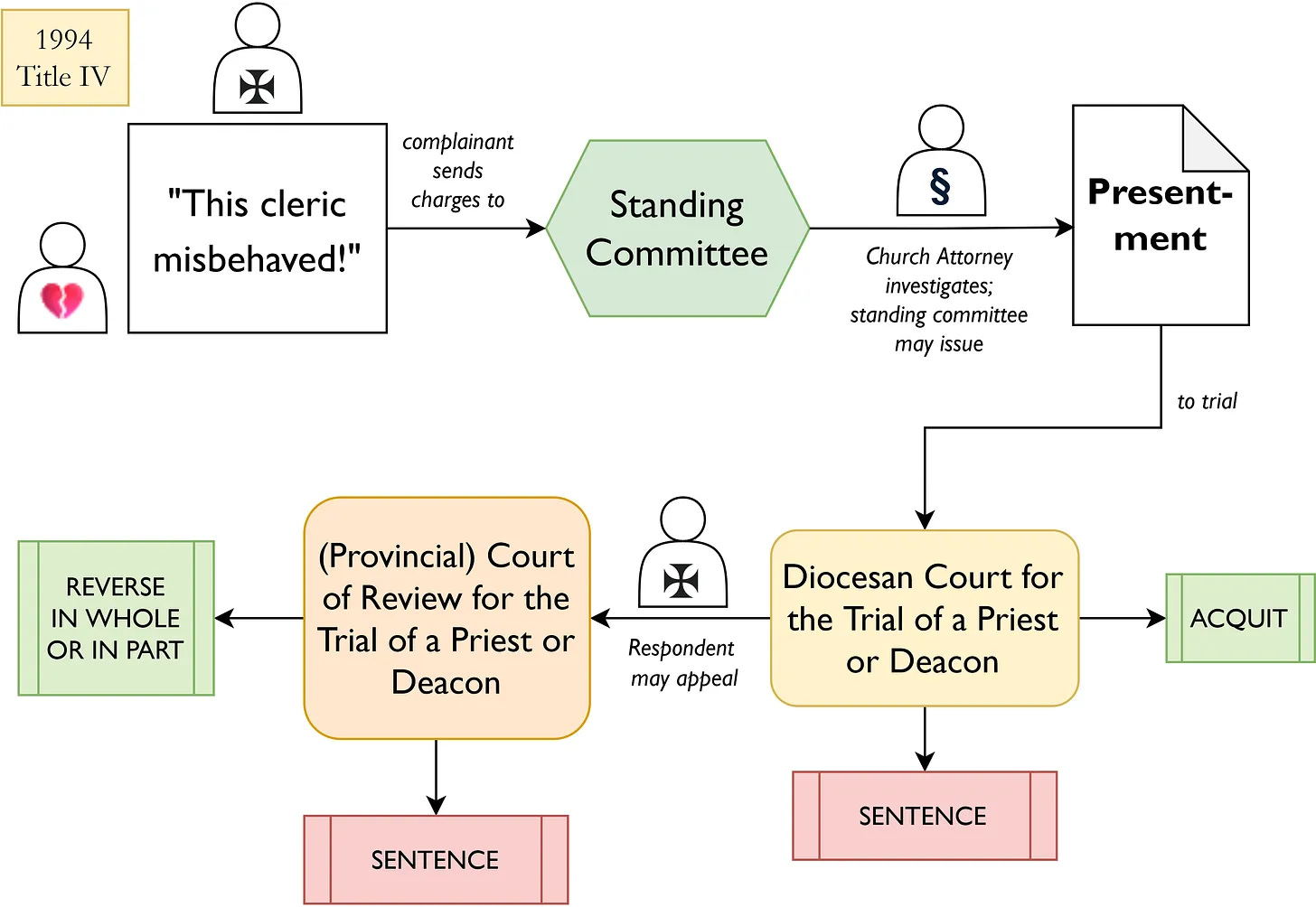

In 1994, the revisions to Title IV created a consistent process for the first time in the Episcopal Church for the charging, presenting (indicting), trying, and sentencing of priests and deacons. This was a major achievement or a major defeat (depending on who you asked), and it sucked all the air out of the room for the years it took to accomplish it. The new canons created a unified process across every diocese in TEC where previously none existed — the old pre-1994 canons only regulated the charging, presenting (indicting), trying, and sentencing of bishops.

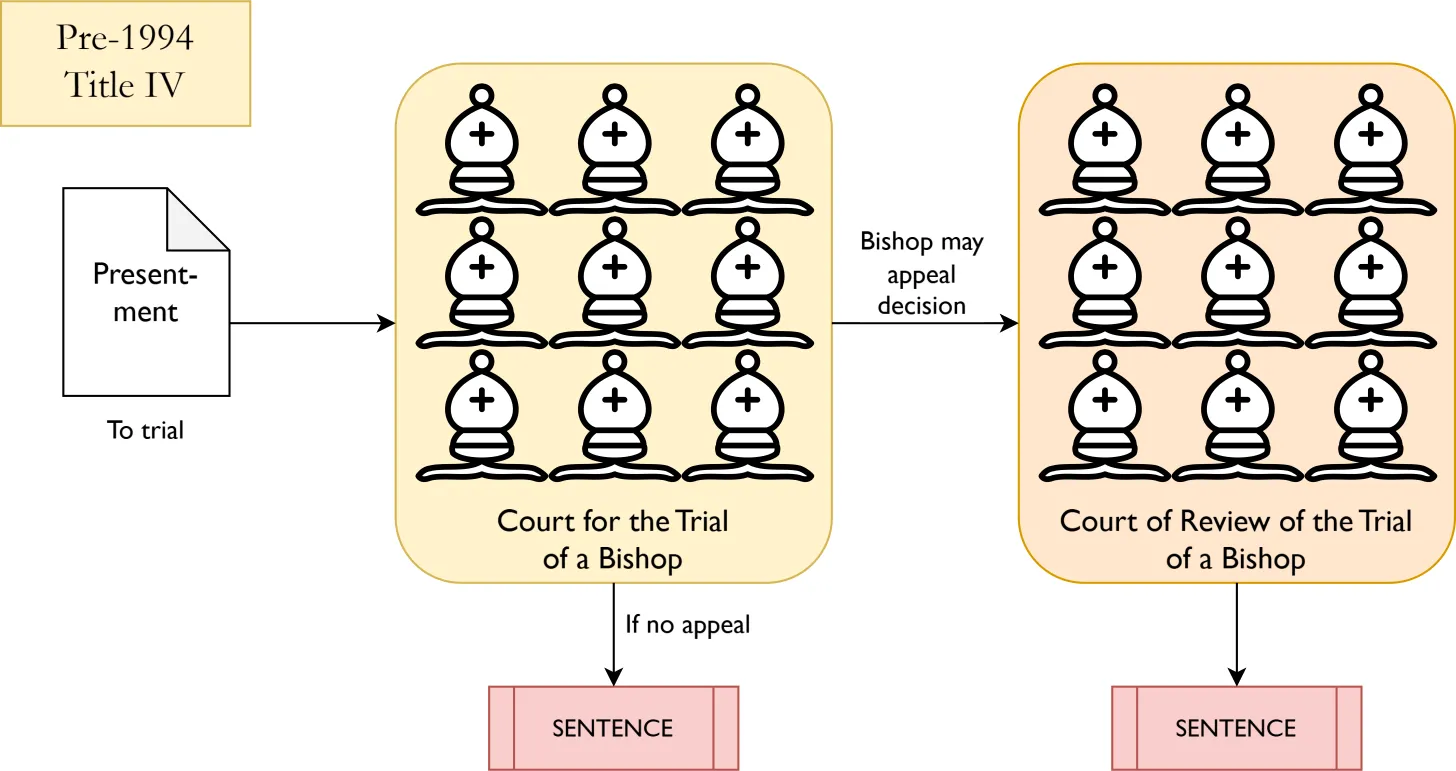

But did you notice, in all of the excitement, that this process for bishops didn’t change? In fact, it remained largely identical to its pre-1994 state, and much of the ethos that informed the choices behind the new 1994 canons for priests and deacons was not reflected in the provisions for bishops.

Let’s recap what this was like.

A recap: Discipline for bishops through 1994

(We’ll reproduce some material from the post on this subject — go there for greater detail if interested!)

Charging and presentment

Before 1994, to pursue a bishop for misconduct, roughly the following process was required:

Charging. You must gather one of two groups to sign onto the charges you’d like to file, and two individuals in the group must swear to the charges:

Three bishops; or

Ten confirmed adult communicants in good standing, including two priests; one priest and six laypeople must be from the diocese of the charged bishop.

Inquiry. Once you’ve got the charges ready, you send them to the Presiding Bishop. The Presiding Bishop assembles 3-7 other bishops, who determine by majority whether, if proved, the charges constitute a canonical offense. If so, they assemble a Board of Inquiry consisting of 5 priests and 5 lay people to investigate the charges.

Presentment. If the majority of the Board of Inquiry finds sufficient grounds for trial, they call the Church Advocate (essentially a prosecutor) to write up a presentment (essentially an indictment), and the matter goes to trial.

This system had, according to some, some features to commend it. Recall that the Presiding Bishop is not a metropolitan in the Episcopal Church, so the 3-7 bishop panel near the beginning of this process is a way to spread the decision-making out from solely the Presiding Bishop. Not only does it avoid a bottleneck at the PB, but it dilutes the voice of the PB among other bishops, lest it become too tyrannical. Similarly, the 3-7 bishops together select the Board of Inquiry, which itself is made of priests and lay people, ostensibly to mitigate bias from having only bishops involved in the process.

But this made for an unwieldy system that did not solve the issues it was designed to. 3-7 bishops, though diluting the weight of the PB, is still quite a number of bishops to get through, especially if you are lodging a complaint about their bishop friend. Moreover, the 3-7 bishop panel and the Board of Inquiry are ad-hoc for each case — what guard is there to ensure the PB does not stack the 3-7 to vote the way he or she wants for a given complaint, or to ensure the 3-7 do not stack the Board of Inquiry to do the same? Worst of all, according to some, was the high bar to even file charges against a bishop in the first place. Especially when TEC had just approved a victim being a sole complainant in cases of crime, immorality, or conduct unbecoming of a priest or deacon, “Why should a victim be required to go and convince three bishops to start a process? [That suggests] we don't believe that when victims bring charges [against bishops] that it is a legitimate complaint.”1

Trial and sentencing

If you were able to get a presentment out of the process so far, then the matter went to trial before the national-level Court for the Trial of a Bishop. Nine other bishops sat on this court, and if they rendered a judgment that the accused wanted to appeal, they could do so to the Court of Review for the Trial of a Bishop — on which nine more bishops sat.

Many perceived this to have a similar problem as the presentment process. Namely, it’s just a lot of bishops. On the one hand, the demands of the episcopate are different than that of other offices, and bishops might be well-suited to assess other bishops’ performance or even take them to task for failures that other people may not grasp. But on the other, every additional bishop in this process is a bishop that might try to cover for his or her accused bishop friend.

What to do?

Discipline for bishops after 1997

A motivating principle of the 1994 revisions was that what’s good for the goose is good for the gander: there was one process for disciplining bishops throughout the church. It was unwieldy, but it was uniform. So too there should be one process for disciplining priests and deacons throughout the church.

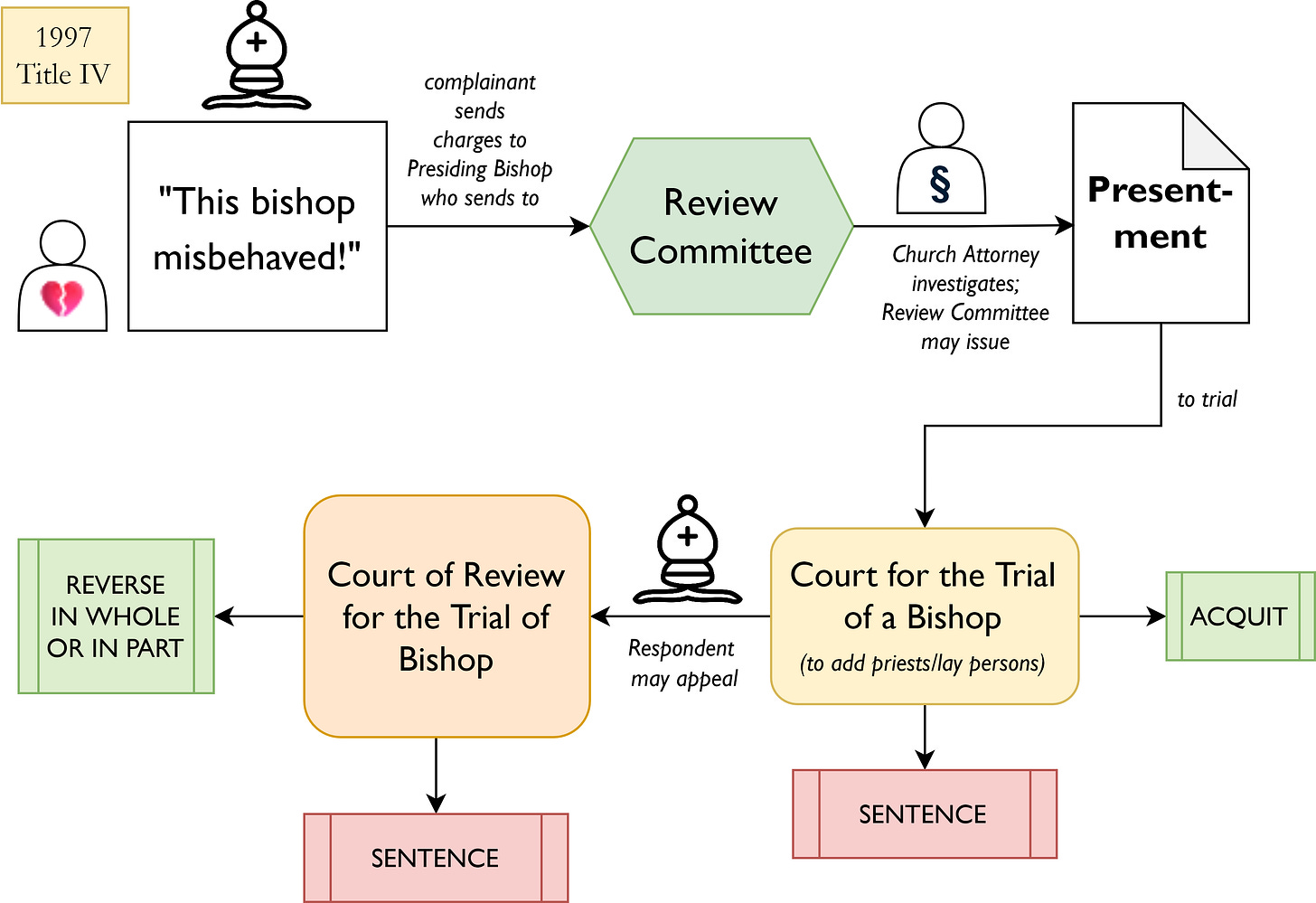

Leading into 1997, General Convention claimed that what was good for the gander was good for the goose too. They introduced several provisions for bishops that the 1994 revisions had introduced for priests and deacons.

Charging and presentment

A clear example of the parallelism sought by the 1997 revisions is the reworking of who may bring charges against a bishop. To the old 3-bishops/10-adult-communicants standard was added a third provision that mirrored the 1994 provision for priests and deacons. Now, charges could also be brought against a bishop

in a case when the Offense alleged is the Offense of Crime, Immorality or Conduct Unbecoming a Member of the Clergy, … by any adult who is (i) the alleged Victim, or (ii) a parent or guardian of an alleged minor Victim or of an alleged Victim who is under a disability, or (iii) the spouse or adult child of an alleged Victim.2

Like for priests and deacons, this made it possible for a single individual to bring charges of clerical abuse against a bishop. No longer would a victim have to convince three other bishops or nine other people to help file.

While the way to make these provisions parallel for priests/deacons and bishops was clear, not all elements were as clear. For example, the 1994 revisions established that all charges against priests/deacons should be sent to the standing committee of the diocese — best to keep the bishop out of deciding whether to prosecute. But, recognizing that many people will not know the canon and will see the bishop as the natural person to complain to, the 1994 revisions also gave a process for the bishop to refer complaints they receive to the standing committee, provide the complainant with an Advocate (to help navigate Title IV), and arrange for their pastoral assistance.3 But what is the parallel to this diocesan situation on the national, bishop level? Bishops don’t themselves have bishops (TEC has no metropolitan), and the national church doesn’t have a standing committee to make the decision of whether to move forward with a disciplinary case.

In pursuit of parallelism, the 1997 revisions, somewhat controversially, invested some of these disciplinary roles in the Presiding Bishop, and counterbalanced them with a new national body called the Review Committee. Here is how it worked.

Like before, you send your charges against a bishop to the Presiding Bishop.4

The Presiding Bishop forwards the charges to the Review Committee if either the complainant or respondent request it (the other option being to let the Presiding Bishop attempt a resolution using his or her soft power).5 The Review Committee is appointed at General Convention, not ad-hoc for the case, and is made up of 5 bishops (selected by the Presiding Bishop), 2 priests, and 2 lay people (selected by the President of the House of Deputies).6

The Review Committee considers the question: “if the facts alleged be true, might an Offense have occurred?” If they determine yes, they call the Church Attorney to investigate.7

After the Church Attorney renders a report back to the Review Committee, the Review Committee considers whether the information, if proved at Trial, provides Reasonable Cause to believe that the bishop committed the Offense.8

In this way, the Review Committee paralleled the role of the standing committee in the case of misconduct charges against a priest/deacon. It also replaced and simplified the 3-7 bishop panel and the Board of Inquiry of the pre-1994 system (“which ha[d] been in the past essentially a duplicate and expensive mini-trial,” according to the SCCC9), while still maintaining non-bishop-clergy and lay representation.

Temporary inhibitions

Under the 1994 revisions, a diocesan bishop could temporarily inhibit (block) the functioning of a cleric for a well-defined reason during some or all of the pendency of the disciplinary process. This non-prejudicial measure was easy to justify: if a cleric has really misbehaved, and has the potential to inflict more harm while the process is unfolding, defining how the bishop may put the cleric on some type of leave until things became clear was accepted as a reasonable move.

But who could inhibit a misbehaving bishop?

Before 1997, the answer was “no one.” Remember, TEC does not have a metropolitan. The Presiding Bishop does not have jurisdiction over other bishops as an inherent part of the office, and other bishops do not inherently owe obedience to the Presiding Bishop. Nor had General Convention ever vested this specific power in anyone canonically: “no one had the authority to restrict a bishop from functioning during the investigation of a complaint. Unless a bishop voluntarily submitted to discipline, nothing much could be done.”10

The 1997 revisions, again not without controversy, decided to give the inhibition power (not jurisdiction writ large) to the Presiding Bishop, with the Review Committee as a check.11 Why the Presiding Bishop, besides he or she being an obvious figurehead? The Standing Commission on Constitution and Canons (SCCC) explained their reasoning:

The Presiding Bishop is often in the best position to evaluate the situation, determine the needs of the Church as a whole, and determine whether a Bishop should be inhibited while allegations are being investigated and resolved. In fact, the Presiding Bishop has been functioning in this way informally despite the lack of any canonical authority to impose restrictions on other Bishops.12

Giving this power explicitly to the Presiding Bishop was thus a regularization of something that was already happening anyway, though inconsistently and opaquely, in the hopes of making it consistent, transparent, and regulated out in the open. “I feel what is going on is extracanonical,” the chair of the SCCC Samuel Allen had said, “and I think we can do better than that.”13

To guard against abuse of the inhibition power by the Presiding Bishop, and in recognition of the fact that that power is not inherent in the solitary office of the Presiding Bishop, the 1997 revisions allow an inhibited bishop to appeal the inhibition to the Review Committee, similarly to how an inhibited priest/deacon can seek relief from their standing committee.14 Additionally, if the inhibited bishop is a diocesan, consent from the majority of that diocese’s standing committee is necessary to effect the inhibition.15

Trial and sentence

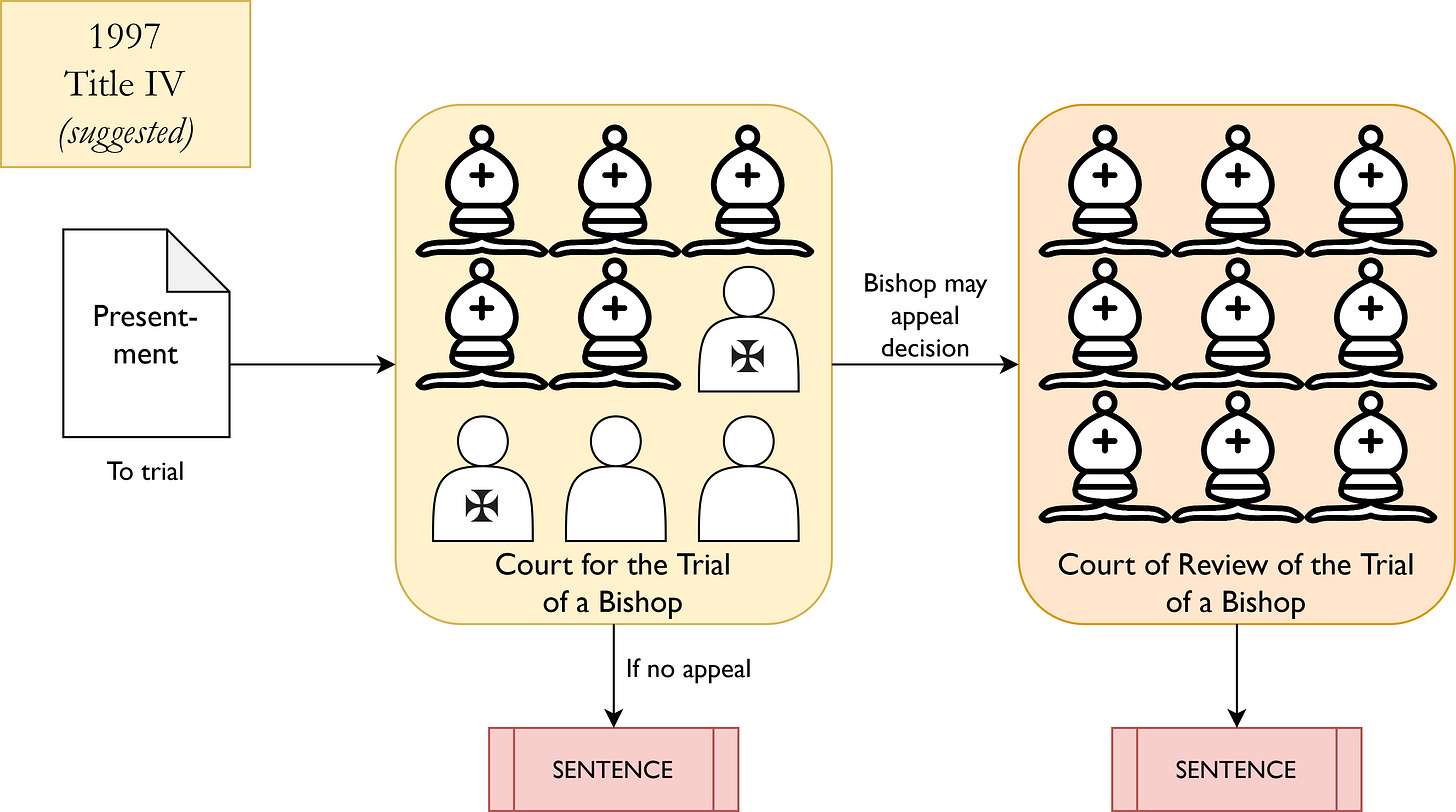

In the interest of holding bishops to account by employing people who are not bishops in the disciplinary process, the 1997 revisions had one more major item up their sleeve. Instead of the 9-bishop Court for the Trial of a Bishop required by the previous canons, the 1997 revisers suggested setting up two such Courts.

One court would be as it had always been: 9 bishops, elected 3 at a time by the House of Bishops at General Convention. This court would be used for trying a bishop accused of “holding and teaching publicly or privately, and advisedly, any doctrine contrary to that held by this Church.”16 This would remain fitting, said the SCCC, since the polity of the Episcopal Church sees bishops as “responsible to judge matters of Doctrine based on their training, experience and their Ordination vows to ‘guard the faith, unity, and discipline of the Church.’”17

But for other offenses, something radical was proposed: the Court for the Trial of a Bishop would be composed of bishops (elected by the House of Bishops), plus priests and lay people (elected by the House of Deputies). This suggestion would, for the first time, have non-bishops judging bishops. Why do this? The SCCC’s reasoning is, again, worth reproducing in full to get an idea of what the church was thinking (bullets mine, for readability):

Having Priests and lay persons serve on the Court for the Trial of a Bishop would more clearly reflect our Baptismal theology that all baptized persons share in and have responsibility for the ministry of the Church by serving on its courts.

It would remind us and embody the fact that Bishops are part of and accountable to the entire Body, not just to their fellow Bishops. Priests and Deacons are tried by courts composed of Priests, Deacons, and lay persons.

The Church and those who have been harmed by the misconduct of Bishops may have more confidence in the decisions of the Court if it is composed of persons who share and are representative of the common life experiences of all members of the Church.18

This proposed change, like the others, was controversial and could not be accomplished simply. The Constitution of the Episcopal Church stated clearly that any “Court for the trial of Bishops… shall be composed of Bishops only.”19 Though this change did end up happening, it therefore had to take a long route:

The SCCC wrote the first resolution detailing the desired Constitutional change: seats on courts for bishops should not be restricted to “bishops only.” This resolution passed the House of Deputies in 1997, but died before getting through the House of Bishops with adjournment.20

In 2000 a version of this resolution passed both the House of Deputies and the House of Bishops.21 But to amend the Constitution in the Episcopal Church, a resolution has to pass two successive General Conventions — so this was only halfway to the change.22

In 2003, the resolution passed its second reading.23 The Constitution was amended!

In 2006, the relevant canonical change could finally be brought: for non-doctrinal offenses, the Court for the Trial of a Bishop would consist of 5 bishops, 2 priests, and 2 lay people.24

Getting non-bishops onto the court was therefore the result of significant, sustained effort. As the SCCC predicted, it was “a hard nut to crack,”25 but after nearly a decade, and not letting interest for the issue lapse between any of the meetings of General Convention, it was eventually cracked.

Putting it all together

Last time, we concluded with a diagram of the 1994 revisions’ general process for priests and deacons:

Let’s compare this now with a similar diagram of the 1997 revisions to the disciplinary process for bishops:

While the 1997 fine-tunings of the 1994 revisions passed General Convention comfortably, they definitely had their supporters and their detractors. Many praised the parity of process that was enacted between bishops and priests/deacons, including the National Network of Episcopal Clergy Associations whose priests and deacons had been concerned about double standards.26 Victims’ advocates and clergy alike seemed to be on more or less the same page about the parity the 1997 revisions enforced.

But some remained uncertain of the new powers given to the Presiding Bishop, checked though they were by other bodies. Still others had other worries. Was parity the right model for priests/deacons vs. bishops, when these classes are not the same? Did this system now weigh too heavily in favor of those bringing accusations?

It’s at this point in our story that we must knock on the door of the TEC-ACNA schism of the 2000s. Differences in opinion about discipline for clerical misconduct27 that emerged during this time, and out of the 1994-1997 revisions to Title IV, would be evident in the disciplinary system penned by the framers of ACNA vs. the trajectory TEC would continue to take in its continuing revisions of Title IV as the churches diverged.

Stick around: next time, we’ll finally dive into ACNA’s Title IV system.

David Skidmore, “Committee Fine Tunes Revisions to Clergy Discipline Canons,” Episcopal News Service, February 8, 1996.

TEC 1997 Constitution & Canons, IV.3.23.a.3.

TEC 1994 Constitution & Canons, IV.3.4-5.

1997 IV.3.24.

1997 IV.3.26.

1997 IV.3.27.

1997 IV.3.41.

1997 IV.3.43.c.

Standing Commission on Constitution and Canons, Reports to the 72nd General Convention, 1997, p. 39.

David Skidmore, “Disciplinary Rules for Bishops Achieve Equity for Clergy,” Episcopal News Service, August 6, 1997.

1997 IV.1.5.a.

Standing Commission on Constitution and Canons, Reports to the 72nd General Convention, 1997, p. 25.

David Skidmore, “Proposed Changes in Disciplinary Canons for Bishops Draws Mixed Response,” Episcopal News Service, September 26, 1996.

1997 IV.1.5.d.

1997 IV.1.5.a.

1997 IV.1.1.c.

Standing Commission on Constitution and Canons, Reports to the 72nd General Convention, 1997, p. 14.

Standing Commission on Constitution and Canons, Reports to the 72nd General Convention, 1997, p. 14.

1997 Article IX.

1997 Article XII.

David Skidmore, “General Convention Will Be Asked to Strengthen Disciplinary Canons for Bishops,” Episcopal News Service, June 6, 1997.

David Skidmore, “Disciplinary Rules for Bishops Achieve Equity for Clergy,” Episcopal News Service, August 6, 1997.

Careful readers will note that this subseries has largely treated only the issue of clergy misconduct strictly speaking, and not the issue of what happens when clergy teach false doctrine or attempt to abandon the church (also treated by Title IV). This is a critical subtopic to understand many canonical aspects of the TEC-ACNA schism and is worth its own treatment. I hope to treat it in future posts, but for now will stay limited to the topic of accusing priests, deacons, and bishops of personal misconduct in the larger sense. Those who know the story well already know that indeed these subjects will inevitably dovetail; please forgive me for any inadequacies in my attempt to separate them for initial educational purposes!

Fascinating story and helpful commentary! Cannot wait for the next installment.